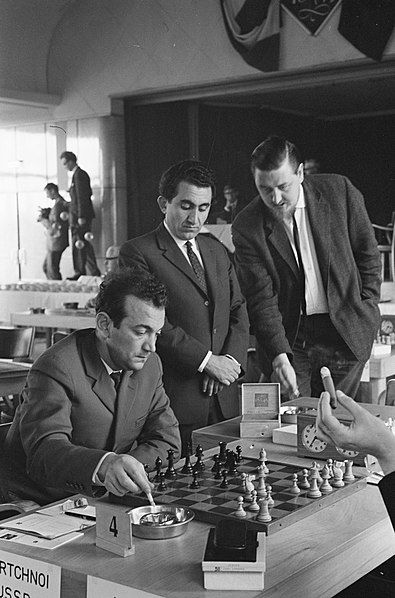

GM Viktor Korchnoi

Bio

GM Viktor Korchnoi (1931-2016) was a Soviet and later Swiss grandmaster who achieved nearly every possible chess success in a roughly 70-year career (approximately from 1945 to 2015) other than a world championship. He played in 10 Candidates tournaments over nearly 30 years from 1962-91, winning two of them but never becoming champion.

Korchnoi was also a four-time Soviet chess champion and five-time Swiss champion, winning his last of the latter in 2011 at the age of 80.

- Early Life And Career

- Grandmaster

- 1962 Candidates

- Future Candidates

- Defection

- 1978 World Championship

- 1981 World Championship

- Later Candidates

- Senior Career

- Legacy

Early Life And Career

Korchnoi learned chess at five years old from his father Lev, who died during the Siege of Leningrad in World War II when Viktor was 10. But Viktor survived and after the war ended, he participated in the Soviet under-18 championship in 1946. Among his opponents was fellow future GM Tigran Petrosian. Korchnoi, 15, lost to the 17-year-old Petrosian. The next year, however, Korchnoi won the Soviet Junior Championship.

Korchnoi earned the Soviets’ master title in 1950 and became an IM in 1954, while earning a degree from Leningrad State University away from the board. Although he did not win the Soviet Championship in this time, he was almost always competitive in it.

Grandmaster

By the mid-1950s, Korchnoi was enjoying international success, culminating with earning his grandmaster title in 1956. These successes included a victory at Bucharest in 1954 and a share of first at Hastings in 1956. He also won a dominating victory, with 17 out of 19, at Leningrad in 1955. However, his results weren’t entirely consistent.

This outcome began to change by 1960 when he won his first Soviet Championship. With 14 points out of 19 (12 wins, 4 draws) he finished half a point ahead of Petrosian and GM Efim Geller.

Here is Korchnoi's victory against Geller (which gave Korchnoi his margin of victory). After an unusual Alekhine's defense, the game turns tactical due to Geller's 13. d5?! Once the skirmish is over, Korchnoi has an attack brewing on white's kingside while White has a strong passed pawn on e7. Geller resigns on move 35 while facing the loss of his queen or checkmate.

Korchnoi finished second in the event in 1961 before winning again in 1962, again with 14/19 and by half a point over two opponents—this time GM Mikhail Tal and GM Mark Taimanov—and again by defeating one of them in their heads-up game.

Here is Korchnoi's victory over the magician from Riga (Tal) in the 1962 Soviet Championship. After a pretty standard Modern Benoni opening, the game turns strategic. Tal rushes his queenside play with 18...b5 and Korchnoi reacts by ripping open the center with 19. e5! By move 23, Korchnoi has a dangerous protected passed pawn on d6 and the bishop pair. The final position is picturesque, with White's connected passed pawns on the 7th rank and a forced mate on the board.

With two wins and a second place in three consecutive years in by far his era’s strongest national championship, Korchnoi had arrived as a top-flight player.

1962 Candidates

Korchnoi’s first Candidates tournament came at Curacao in 1962 for the right to challenge World Champion GM Mikhail Botvinnik. Korchnoi had qualified with a 14/22 score in the Stockholm Interzonal earlier that year.

At the Candidates, Korchnoi scored an even 13.5/27, which only finished fifth in the eight-player field and was four points behind the winner, Petrosian, who went on to defeat Botvinnik for the crown.

Korchnoi actually led early before five losses in the middle rounds knocked him out of contention. He still played some of his best games in the tournament, including the following game against a certain American prodigy, GM Bobby Fischer.

In this game, Fischer plays the aggressive Austrian attack versus Korchnoi's Pirc defense. Fischer plays the bold, but unsound, 13. g4 which Korchnoi pounces on immediately by capturing it on the spot! Korchnoi has a material advantage a few moves later and never releases the pressure on young Fischer.

This Candidates tourney became notorious for a probable drawing pact between the top three finishers, probable enough that the format of the tournament was changed. Fischer, who finished fourth, alleged in an article for "Sports Illustrated" soon after the tournament that Korchnoi threw games as well. But one neither imagines a personality like Korchnoi acquiescing to lose on purpose, nor did he ever in his life suggest that he had been asked to.

Future Candidates

Korchnoi dominated the 1964-65 Soviet Championship, losing none of his 19 contests and winning by two points over GM David Bronstein. Here is Korchnoi's victory over Bronstein in this tournament—a classic heavy-piece ending. After a quiet Ruy Lopez exchange variation, the minor pieces are all exchanged very quickly. Korchnoi puts the pressure on Bronstein's e5 pawn until Bronstein feels obligated to release the tension with exf4. A few moves later, Korchnoi wins Bronstein's queen and it is all over.

However, Korchnoi failed to qualify for even the 1965 Interzonal and therefore missed out on the Candidates. It would be the last time he ever tried for and failed to reach a Candidates tournament.

Korchnoi came back strong the next cycle, finishing second in the 1967 Interzonal in Tunisia to advance to his second Candidates. It went far better than his first try, but after advancing to the finals with match wins over GM Samuel Reshevsky and former world champion Tal, Korchnoi ran into the winner of the previous Candidates, GM Boris Spassky, and lost.

Here is another Korchnoi victory against Tal. This game is from their 1968 Candidates match. Tal has a small advantage in the Ruy Lopez until he plays 23. b3, allowing 23...Nxc3! After Korchnoi's 30...e3, it is difficult to play the position for White, and Tal resigns 6 moves later with all of Korchnoi's pieces active.

In the 1972 cycle ultimately won by Fischer, Korchnoi did not play the American who was beating both GM Bent Larsen and Taimanov 6-0. Rather, after easily defeating Geller, Korchnoi was stopped by Petrosian in the semifinal.

Between cycles, Korchnoi won his fourth and final Soviet championship in 1970. It wasn’t as strong as usual with the champions Tal, Petrosian, and Spassky not playing. Korchnoi won by 1.5 points ahead of GM Vladimir Tukmakov while a certain 19-year-old GM finished tied for fifth.

Here is Korchnoi's game against Karpov from this tournament. After Korchnoi's 13. Rfd1, it is evident that Korchnoi has outplayed Karpov in the opening: Korchnoi has a development advantage and his pieces are far more active. Karpov fought back and by move 23 the position is level and continues to be for a long time. Karpov misses the exchange sacrifice on move 40, and afterward Korchnoi displays fantastic technique to dispatch the future world champion.

The 1975 world championship cycle found Korchnoi in the finals of the Candidates for the second time in three attempts. He reached the Candidates with a victory at the 1973 Interzonal in Leningrad, where his margin was a tiebreaker against the up-and-coming GM Anatoly Karpov—that fifth place finisher from the 1970 Soviet championship—who also qualified. While Korchnoi was beating GM Henrique Mecking and Petrosian in the Candidates, Karpov defeated GM Lev Polugaevsky and Spassky, setting up a showdown in Moscow.

This final was draw-heavy with 15 of the first 18 games ending in an equal result. Unfortunately for Korchnoi, the other three were all losses—in the second, sixth, and 17th games. Korchnoi did close the gap to a single point with wins in games 19 and 21—the latter of which was a 19-move rout—but never broke through again. Here is game 21 of their match, where Karpov collapsed quickly. After Korchnoi's 13. Nxh7!, it is virtually impossible to hold the black position.

Fischer, of course, did not play to defend his title against Karpov. It can’t be said for sure whether he’d have made the same decision against Korchnoi.

However, the 1974 Candidates final appears to have been Korchnoi’s first great chance at becoming world champion. It would not be his last. In the meantime, there would be plenty of drama away from the board.

Defection

Korchnoi was not the most popular player within the Soviet political establishment, and he also failed to get along personally with several players, including '60s champions Petrosian and Spassky. After winning a tournament at Amsterdam in 1976, Korchnoi did not return home. Disagreements with Karpov came after Korchnoi's defection and were manifested in their championship matches to come.

Korchnoi would later tell the British newspaper The Guardian in 2009: “When I defected it was because of chess, not politics. I wanted to be a free person. Freedom is my essential stance.”

This decision began a period where Korchnoi had no home nation until becoming a citizen of Switzerland in 1980. All while his wife and son, still living in the U.S.S.R., were not allowed by the government to leave. (They defected in 1982.) Not to mention there was still chess to be played.

1978 World Championship

The closest Korchnoi ever came to shedding the “never champion” label was in the 1976-78 cycle. As the loser of the 1974 Candidates, Korchnoi had an automatic bid into the 1977 Candidates. (It receives less attention than 1975, but Fischer had a bid as well, which he unsurprisingly declined.)

Korchnoi again defeated Petrosian, this time in the quarterfinal. Then he stopped Polugaevsky to again reach the final, setting up a rematch of the final from nine years earlier against Spassky. This time Korchnoi beat his rival by a score of 10.5-7.5 (fending off a large comeback attempt by Spassky, who won games 11-14) to set up a matchup with another rival: Karpov.

Here is one of Korchnoi's victories against Spassky from their 1977 Candidates match. After a French Winawer opening, the game turns sharp. Many pieces are exchanged in the early middlegame, resulting in a heavy-piece endgame. By move 22, Korchnoi establishes a rook on the second rank but the position remains level. On move 36, Spassky stops defending well and this time Korchnoi's attack is unstoppable.

Korchnoi was vying to be the first stateless champion. As in 1974, a comeback fell just short. Whereas the 1974 match had been a best-of-24, the 1977 Championship was the first to six wins.

After seven draws to start, Karpov won the eighth game, but Korchnoi tied the match in the 11th game. Unfortunately for him, as in 1974, he fell behind three points by game 17, leaving Karpov two wins from defending his title. Of the next nine games, eight were drawn with Korchnoi narrowing the gap to 4-2 in game 21.

When Karpov went up 5-2 in game 27, Korchnoi started to roar back, claiming games 28, 29, and 31 to make it a 5-5 match. Here is the 31st game, where Korchnoi evened the match. Korchnoi plays a Queen's Gambit exchange variation and gets the Carlsbad pawn structure in the endgame. Playing with the minority attack on the queenside, he tries to outmaneuver Karpov but he can't make any headway. In the rook and pawn endgame, Korchnoi goes for a pawn sacrifice to get his king active on the queenside with 52. a6! On move 58, Karpov makes a mistake that Korchnoi punishes relentlessly! A very instructive endgame.

The next player to win would be the champion, but the drama did not last long—Karpov won the 32nd game to defend his title. The 1978 World Championship may have been the oddest in history—not just in that one player had no home nation. Perhaps the most infamous moment came in the second game, a typical draw on the scoresheet. Karpov received a yogurt in the middle of the game, and Korchnoi's team protested that it could have been intended to tell Karpov how to proceed in the contest. Korchnoi's side would later claim it was mostly a joke, but it still demonstrated the tension in this match.

1981 World Championship

Korchnoi’s overall score in the 1977 Candidates had been 26.5-17.5, but in 1980, the score was much closer at 17.5-13.5. He defeated Petrosian by two points and Portisch by one to reach his third consecutive final, this time against West Germany’s GM Robert Huebner. Korchnoi fell behind early, but Huebner lost the seventh game in dramatic fashion and then the eighth as well, and forfeited. It was somewhat anticlimactic, but Korchnoi was again a match away from the title.

Karpov won three of their first four games and was off to the races. Korchnoi’s rebound in game 6 was wiped out by a loss in game 9, and the same happened when Korchnoi won the 13th game and lost the 14th. Karpov achieved his sixth victory in game 18, ending this match 14 games earlier than their 1978 bout.

Later Candidates

Korchnoi never played again for the world championship despite successfully reaching four more Candidates events consecutively, during the 1984-93 cycles. The 1983 Candidates was his fourth championship run in a row and fifth overall to end against the eventual champion, as he fell to GM Garry Kasparov in the semifinal. That match, scheduled to be played in Pasadena, California, almost didn’t happen for political reasons, but Korchnoi agreed to play in London instead. He wasn’t very competitive but did record what would be his only win against Kasparov.

In this game, Korchnoi plays an unorthodox double fianchetto Queen's Indian defense as Black. Korchnoi sacrifices a pawn on move 14, which Kasparov returns shortly after. The endgame that occurs after the queen exchange on move 25 looks equal, but Korchnoi pushes and outplays his legendary opponent. Korchnoi wins a pawn on move 35 and uses this outside passed pawn to deflect Kasparov's king to the queenside. Korchnoi's connected central passed pawns are too much for Kasparov to handle.

In 1991, Korchnoi reached the quaterfinal Candidates match at the age of 60. When the championship fell into disunity, however, he did not compete for either title except the 2002 FIDE knockout where he lost in the first round.

Senior Career

Even then Korchnoi’s career was far from over. He had won three Swiss championships in the 1980s (1982, ’84, and ’87) and then won twice more over the next 20 years in 2009 and ’11. The latter two came at the ages of 78 and 80, when some players have been retired for multiple decades.

Korchnoi was also victorious in the Senior World Championship in 2006. He was 75 when the minimum age for entry was 60, yet his chess faculties were still perfectly strong. He claimed seven wins while not losing any of 11 games.

In 2011 he turned 80 and won his final Swiss championship. Korchnoi also played in Tradewise Gibraltar (+3 -1 =6), the senior division of the Botvinnik Memorial (+5 -0 =4 in a full-point victory), the European Club Cup (+3 -1 =3), and the European Team Championship (his only sub-.500 tournament performance of the year at +1 -2 =5). He was more active at 80 than many players half his age.

In his ninth decade of life, Korchnoi’s health finally began to fail. He passed in June 2016, and the tributes were many as these examples illustrate: Chess.com, Kasparov, Serper, and Russian media.

Legacy

Korchnoi may never have become the world champion, but he had a winning record against four of them (Tal, Petrosian, and Spassky in large samples, and a 13-year-old GM Magnus Carlsen in their single matchup in 2004) and was even against two (Botvinnik and Fischer).

No one style of play defined Korchnoi's chess. He won against Tal's attacks, Petrosian's prophylaxis, and Spassky's universality. He was also a fighter, playing fewer draws than most grandmasters of his time or others. That fighting spirit certainly showed up away from the board as well.

Although players are getting better quicker, Korchnoi was still a late bloomer by the standards of his day. He didn’t play in a Candidates until 1962, when he was 29; Bronstein won that event in 1950 when he was 26 while Tal set the record for a champion at 23 in 1960. Korchnoi showed another path.

And whatever Korchnoi may have missed out on in his 20s, he made up for with an immensely successful, 70-year career. He became widely admired despite his cantankerous personality. A giant of the chess world, his life was about more than chess as well given the personal and political risks he took in defecting from the Soviet Union.

It’s a phrase often used, but it applies to Korchnoi perhaps more than to any other player in the history of chess: one of the best to never become the world champion.